Interview

Shehan Karunatilaka: beyond the afterlife

Booker Prize-winning author and creative director on rewrites and rejection

Almost a year ago, his latest novel won one of the world’s top literary prizes, more than a decade on from his previous prize-winning book. In the years before, during and since, he has had another life as a much-traveled advertising creative director. From his home in Colombo he renews a long acquaintance with Lürzer’s Archive … and ranges across his diversified career.

This feature is from Lurzer’s Archive Volume 03/2023

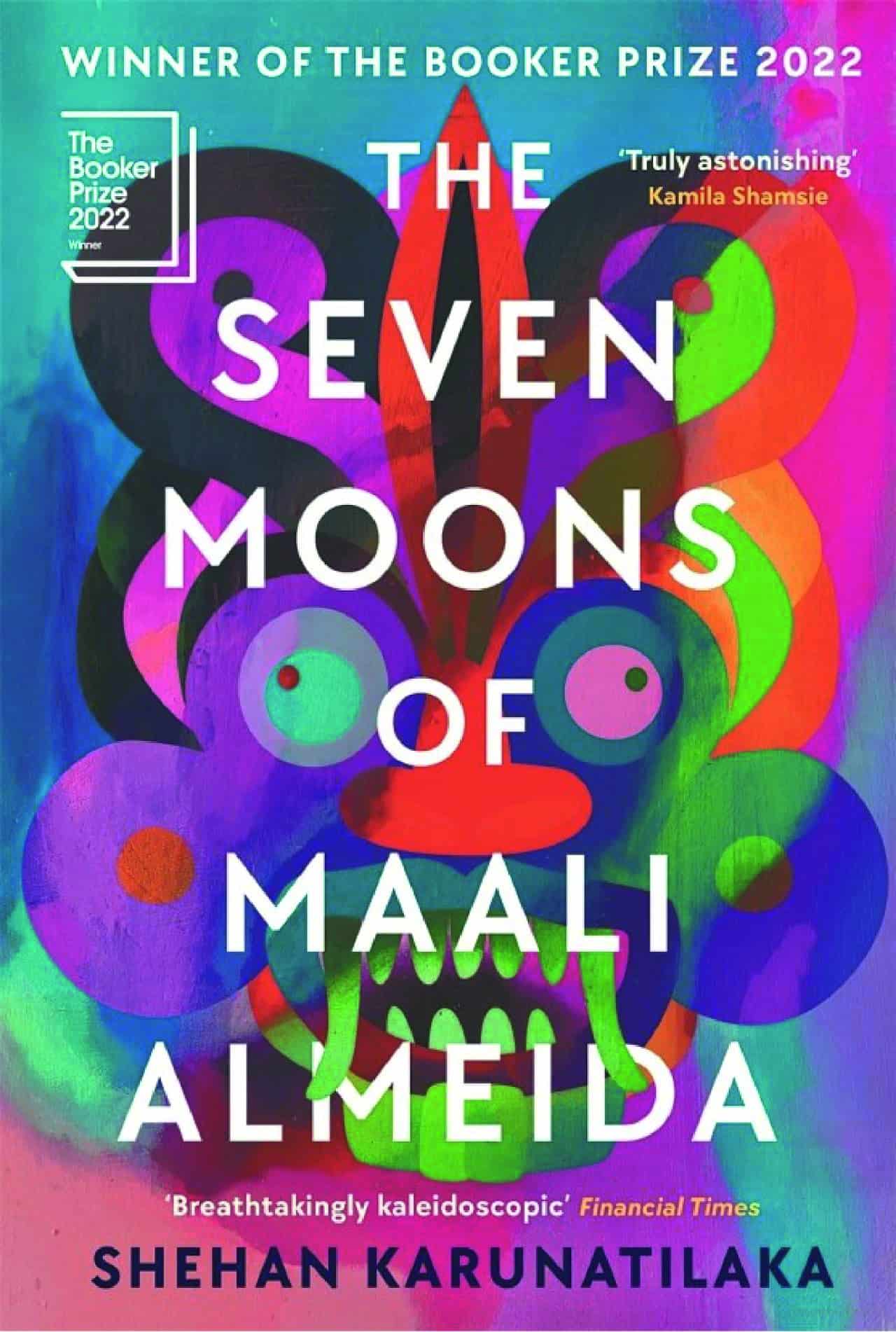

When The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida won the Booker Prize in November 2022, it pushed a novel that had struggled for publication into the forefront of literary discussion worldwide. The author, Shehan Karunatilaka, was only the second Sri Lankan to win the award (after Michael Ondaatje, writer of The English Patient).

While Karunatilaka was unknown to most of the global reading public, he had serious form. A decade before, his first novel, Chinaman, had picked up internationally important prizes and the acclaim of being listed as one of the very greatest cricket books ever by Wisden, no less (for the uninitiated, the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack is seen as the ultimate authority on cricket). So, what happened? Why not a steady and continually rising profile?

Life in general happened and earning a living in advertising, then Covid … much got in Karunatilaka’s way. Out of this lengthy gestation a book finally emerged that is a darkly comedic and savage tale, which after a final rewrite and a name change became The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida. In this now much-acclaimed masterpiece Karunatilaka examines the terrifying times of the Sri Lankan civil war through a unique, complex imagining of the afterlife, a distinct mix of some familiar elements from various sources that is ultimately entirely unique. It is a device that enables Seven Moons to shed light on a gruesome history and the wider human condition while telling a fast-paced tale from the perspective of a murdered photographer. This much-troubled narrator, a man with messy relationships and a bad gambling habit, has a secret stash of compromising war images that he somehow needs to release into the world and try to right some wrongs … and even death can’t be allowed to stand in the way.

The process that led to the book, one of extensive research, creation and destruction, owed something to the writer’s even longer (and continuing) career as a creative director, where rejection and rewriting can be an almost everyday occurrence. Once you know the writer’s background (and indeed, somewhat ongoing career) the novel starts to have other possible readings.

Lürzer’s Archive went in search of the author and found a charming man who still freelances his creative talents internationally among agencies while working on his own children’s book publishing house, while playing and learning a range of musical instruments for fun … and all while developing the next big book. We will have to wait for that but let’s dive into a diverting conversation.

L[A] Shehan, where are you at the moment?

SK I’m back in Colombo, in Sri Lanka at the same desk where I wrote the books. No more travel for a little while … It’s been a hectic few months of travel. I’m here till the circus begins again.

L[A] Where do you go then?

SK There’s a European tour happening. I’ll be in Edinburgh and London and a few other cities. The book is being published in Greek, in Italian, in German and …

L[A] It has been a very different year.

SK Yes … and now Archive magazine! I’ve got some issues of the magazine around me here somewhere. I remember the time a few years ago when Basheer bookshop in Singapore had loads of copies and we were all obsessed with Lürzer’s and about getting into the Archive.

L[A] What were you doing then?

SK I was a creative group head at BBDO Singapore. I had published the first book, Chinaman, and had quit advertising for a while but then went back in after a few years out.

When I first gave up advertising work, it was because I had this idea for Chinaman. I was living with my parents. I had a bit of money in the bank. So I could afford to take off for six months, which is what I thought it would take to write. It ended up being three years.

It was fairly common as well back in the day that every copywriter had a little screenplay, novel, or TV show. Now I guess, it’ll be a TV show or video game or podcast idea they are working on. And every art director was a secret filmmaker, painter, all that. We had our other careers in mind because, you know, advertising is, or was, seen as a young person’s game.

When you’re in your 20s, you’re keen to win awards or to win a pitch. You sacrifice your weekends. Especially in Singapore, you’re expected to work till nine, ten, eleven every day. As you get on and have a family, these things start to matter less and less. But for a while, I was in that game.

L[A] What took you back into advertising?

SK When Chinaman finally came out, although initially self-published, it did better than I expected. It eventually got published in the UK, it even got published in the US. It did reasonably well in the subcontinent and was critically acclaimed. It won some prizes. But I still had to work as a copywriter. I’d get a paycheck every year for the book. With that, I might be able to go on a holiday or take friends out for dinner, but that was kind of it from three years of work on the book. I still had to do my job! I might work on a little pitch over a week or a couple of weeks and earn the same money as the book made in a year. That was kind of depressing.

Everyone wants to write, everyone wants to shoot films. I was pretty certain I wanted to keep writing. I just had to figure out a way to balance my career and writing. So 2013/2014, then I was back in advertising at BBDO in Singapore. My wife and I were expecting our first child and that’s when we made the decision to come back to Sri Lanka. Otherwise, we’d be stuck in Singapore and both of us working – she as an art director – and with jobs and two kids in daycare, there was certainly no novel writing time. We came back to Sri Lanka with the idea of being able to freelance. That’s what I did right up until Covid. Same with my wife. She got into interior design. I still commute to Singapore.

L[A] So, you were freelancing back to Singapore but living in Colombo?

SK Yes. I liked Singapore a lot more when it was just for some months, when I wasn’t paying Singapore rents all year. It is one of the most expensive cities in the world. January to April, I’d go. I freelanced around the block. So, JWT, Y&R. BBH – had a couple of stints there – Iris, BBDO, Grey … I even did a few months at Facebook. I would come in as a gun-for-hire copywriter. Four months of a Singapore salary is pretty good when you come back to Sri Lanka, especially now with the Sri Lankan rupee completely tanking. That worked out for a while. May till December was when I wrote. I worked that way for several years, on Seven Moons and some short stories.

I also started a kids book business, Papaya Books, with my brother. We figured that because something like The Very Hungry Caterpillar sells a million copies every year this was good business to get into. I mean, all respect to the legendary Eric Carle who wrote it but I read it and thought, ‘we could knock this out in an afternoon!’ Yes, some children’s books are real masterpieces and I could never write like that. But I was reading Hungry Caterpillar and telling my brother, ‘You could draw this. I could write it … there’s not much plot here. It’s a caterpillar who eats a lot of stuff – a lot of bad food, by the way – then becomes a butterfly.’ I thought, ‘Forget writing literary novels, which people may or may not read, may or may not publish.’ That was the beginning of Papaya Books. We are working on two books at the moment. One is about bugs.

L[A] How did you get back to the focus of writing a novel, and taking it to the global award level of Seven Moons?

SK Papaya was a fun business project, two books a year. Meanwhile, Chinaman had a life in the sense that it developed a cult following. It got optioned for film. Nothing much really happened. Agency life didn’t fully suck me in but if I’m being honest, I only got the work balance right during Covid because up till 2019 … well, we also had young kids. They are nine and six now but they were one and three at one point. So, I can blame all these excuses for slowing down my novel writing. When Covid came, I kind of panicked. The planes weren’t flying. I couldn’t go to Singapore to earn my freelance living. It usually happened by December, that I was broke … but now I couldn’t go to Singapore. December 2019, big Christmas, I was broke. So OK, let’s take the novel and try again, I thought. In all, Seven Moons took seven years.

So I could afford to take off for six months, which is what I thought it would take to write. It ended up being three years.

I wrote a draft over three years, then realized it was … well, not right. I went through three further rewrites and many title changes [Shehan explains the challenging and long process of working with an old friend who became his editor, Nat Jansz. It was her publishing company Sort Of Books, founded with her husband Mark Ellingham, that would go on to finally publish the novel]. During Covid I wondered ‘Am I going to have to get a proper job now? What’s going to happen?’ But clients were still there and, as you know, everyone moved to working remotely.

And it continues that way. Even now. I just had a briefing with Superson, a Finnish agency I work with through their Singapore office. When Covid came along I had about three or four agencies where I knew people I’d worked with – at BBDO, McCann, wherever – and who had now formed their own agencies. I know Covid was a terrible time for the world but we managed to stay healthy and stay indoors and just read all the unread books in our house while still having some work.

With work from home, I realized I didn’t have to just work from January to April. I could balance clients and ongoing work with writing. I could dictate that I work two or three days a week. That was ideal I think, and perhaps was my greatest moment over the last 15 years in writing. I mean, the book is obviously up there, but not the top five certainly. I think the greatest moment was when I realized I could keep writing. I didn’t know it was going to win a Booker Prize or even get long-listed but the great moment was when I realized I could still work on the book and finish it. If it gets reviewed, if it’s liked, fine. If it doesn’t, I’ll get over it. But I can write another one and another one and sustain this. I didn’t have to deal with that anxiety that we all have when we’re writing.

All that balance, all those questions went out the window because I saw I could just work as much as I needed to. Bills can get paid and the book doesn’t have to become a bestseller for me to justify myself. It can have its own life and I can keep writing. Even when the Booker win happened I had a few clients going on at the time with work to finish. I had to say, ‘Hey, guys I need to take a break…’ because I was traveling non-stop. But that’s settled down. I had a briefing this morning and I think I might have one tomorrow. I’m keeping the advertising work going.

L[A] You obviously have a great creative need, which perhaps includes needing diversity in the work. Was it very early on that you knew you wanted to write a novel?

SK No. I started out more with other aspirations. You see the messy room I work in? There’s a keyboard there. There’s the drum kit and there’s a Telecaster, a couple of acoustic guitars. There are six guitars, the keyboard and the drum kit. I’m not a particularly talented musician. I mean, I love music. In my 20s, I was playing in bands, a bass player then. With typical male fantasies of making it in music. Back then when the music business wasn’t broken. ‘Yeah, I’m going to be a rock star and travel the world and make millions.’ Now, I don’t think kids are thinking about being rock stars because I have hardly heard a guitar-based band in the last 10 years.

L[A] Do you play in a band at all these days?

SK Well, that’s the only thing missing. My son’s learning drums so I’m kind of learning drums as well. I’m teaching myself the piano and teaching myself the drums during writing – as a break, as a fun thing.

That said, I think I’m pretty close to forming a midlife crisis band. There are enough 40-50-year-olds that we’ve been having conversations. I think that could happen … but the bands I have been in always have better names than the actual sound of the music.

L[A] Give us a name.

SK Power Cut Circus was the last band. We are thinking of resurrecting it because it’s quite apt now in Sri Lanka. Power Cut Circus was formed during the power cuts of 2005 after the tsunami. Music was a first love and advertising was initially just a way to get my old man off my back. He was always asking, ‘What are you going to do with the English degree? You should have done accountancy or economics.’ He was a doctor. I think MBAs were in fashion then and he would say, ‘Do your MBA.’ I did English, philosophy and history. I think advertising was my way of saying, ‘Well, you can have a different kind of career.’

L[A] And then?

SK My bands got nowhere but advertising … I was at McCann Colombo in my 20s and got to group head level. Then, as soon as you became a group head or senior writer, you could ask for a car. That was a big status symbol in Sri Lanka. I’m 25 and driving a car! That kind of got my old man off my back. But the thing is this now, and I can only say it when I’m looking back, I didn’t become a great musician because I didn’t practice guitar every day. I practiced when I needed to play a gig but the great musicians I know are obsessed. They have to play the piano every day.

But I wrote every day. I didn’t do any of the other stuff but just even when I was doing my advertising stuff I wrote. I had a diary and I’d jot down ideas for films, for stories. And then I’d work on a few of those stories when I was bored. I think that came after I had been to London. I worked in London for about three or four years. I was at Springer & Jacoby then I was at an agency called Boy Meets Girl. It was a very interesting time.

In 2002 I joined Boy Meets Girl. I think 2005 was when it went bankrupt. That last year was very stressful because my work permit was tied to the firm. One by one, you’d see people leave … the CD would get fired, the account manager would walk out. The accountant would walk out. The computers were taken away. I never got fired from that firm but my mates got fired. I was probably too junior to matter. I stayed till the ship went down but I was, meanwhile, making notes and I remember thinking, ‘This could make a good novel, the demise of an agency.’ I haven’t written that novel yet. I might.

L[A] On that point, we will have to leave Shehan speculating. He told us much more besides in the interview but perhaps he can tell us it again, reworked in a novel. Talking to him sent us, of course, to look again at his Booker-winning novel. In the epigraph to the second section we found the words that summarize the swirling majesty of the book and may summarize the endless potential edits for this interview around Karunatilaka’s own work and life.

They are not his words but a thought-provoking selection from George Bernard Shaw: ‘Everything happens to everybody sooner or later if there is time enough.’

If that seems intriguing, do read the rest of the book.